“There is a fact: White men consider themselves superior to black men. There is another fact: Black men want to prove to white men, at all costs, the richness of their thought, the equal value of their intellect. To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture. The Antilles Negro who wants to be white will be whiter as he gains greater mastery of the cultural tool that language is…The fact of having to speak nothing but the other’s language when the other was the conqueror, ruler, and oppressor was at once an affirmation of him, his worldview, and his values; a concession to his framework; an estrangement from one’s history, values and outlook.” – Frantz Fanon, In Black Skin, White Masks

“You know, it’s not the world that was my oppressor, because what the world does to you, if the world does it to you long enough and effectively enough, you begin to do to yourself.” – James Baldwin

I had a conversation recently that made me think about decisions we make on a daily basis. It took me back to a lesson I once taught my students. I called it TDA (Thoughts, Decisions, Actions). The basic premise is that all of our actions, all of the things we do begin as a thought or cognition. These thoughts lead us to make decisions, which eventually culminate in action. I told the students that negative thoughts lead to poor decisions and actions that may be detrimental to us. By the same token, positive thoughts lead to good decisions and actions that help us.

This was a lesson I taught to sixth graders early in my teaching career. For the mind of impressionable sixth graders it probably made perfect sense. What I realized later is that life is not this simple for those sixth graders, as they get older. Life has a way of turning sense into non-sense.

I have studied America and life in America for many years. I have learned a great deal about the nuances, cracks and crevices, and other grey areas of the lived experiences of Americans. Most of what I have learned I did not learn in school. Independent reading and research has been my greatest teacher. I can control my learning by taking the paths I choose, not those dictated by our school system. K-12 schools are very deliberate in what track our learning should be on. College was also very restrictive in the pathways I was allowed to gain knowledge in.

It is when I was able to get outside of these systems that I began to gain a clear understanding of the world around me. I was able to see outside the White Racial Frame that sociologist Joe Feagin talked about. That frame of reference is the one all of us are exposed to our entire lives. We are taught to see the world from a very specific, regimented, Eurocentric perspective. We value things and – most importantly – people based on this White Racial Frame.

There was this song I heard people singing when I was a child. This is what it said: “If you white, you alright, if you brown, stick around, but if you black, step back.”

I never thought about the meaning of that little song as a child, when I heard it. I have no idea where the song came from. What I do know is that it was something that planted a seed in my mind. It taught me that to be black was somehow a problem.

Famed sociologist W.E.B. Dubois wrote his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. Speaking of the so-called “Negro Problem,” DuBois talked about how whites inquired about his blackness.

“They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.”

He goes on to say “And yet, being a problem is a strange experience, peculiar even for one who has never been anything else.” I think about this when I look back on my childhood. I grew up in the segregated South. In my hometown in Mississippi there were separate spaces for white and black children to play in. The swimming pool I swam in was not the same one the white classmates of mine swam in. We apparently never thought of swimming in the other’s pool. There were no signs but we knew which pool was ours and which one was for them.

We live in segregated spaces that are often determined by what we call race. We are told that people self segregate, which is simply not true. Richard Rothstein’s incredible book The Color of Law tells the story of how federal, state, and local governments created, over many decades, segregated spaces that still exist to this day. What was unique about how they generally did this was to create exclusive zones meant for whites only. They did not care if blacks and Puerto Ricans or Chinese or Native Americans lived together as long as they were kept out of white neighborhoods.

Even marriage laws known as anti-miscegenation laws in over thirty states dictated who was “allowed” to marry a white person. Much like the segregation policies, these laws made no such rules about who could marry people of color. The whites that promoted these policies and wrote these laws did not care about who married people of color as long as they were not white.

What did these things tell us about people of color? For those who paid attention in even the most casual way, it was abundantly clear that being white was a specially and elevated class in America. Whites were protected and promoted as the example of what other people should live up to. To be white was to be right.

For those on the outside looking in, there developed for some a strong desire to fit into the white norm. For others, the situation was forced upon them. Native American children were taken from their families and placed in so-called boarding schools and “whitened up.” They had their hair cut. They were not allowed to speak their native language or wear their traditional clothing. They were forcibly and systematically turned into mock white children.

Of course, the process of assimilation was without parental consent. There was little or nothing they or their parents could do to fight this system. The federal government opined that they were doing these children and their families a favor by taking the “savage” out of them. To be as close to white as possible was somehow better they were told.

One of the black heroes I was taught about as a young student was Booker T. Washington. I think I heard more about his greatness than anyone else including Dr. King. He was the shining example of a good black person. I did not get it until later that he was an assimilationist. His most famous public address was given in Atlanta in 1895. It is known as the Atlanta Exposition Address. In his speech, Washington expounded on the idea of separation of the races. The most famous words of this speech were:

“In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

His main idea was that black people were pushing too hard for social integration. The white crowd responded with thunderous applause, but Washington was challenged by many including Du Bois for “an apparent endorsement of racial separation in favor of economic opportunity,” and as an accommodationist with the white Jim Crow system.

Du Bois and other critics of Washington wanted nothing to do with legal segregation. As an elementary school student I was told Booker T. Washington was the greatest black man that had ever lived in this country. I was taught to celebrate his non-confrontational style of racial accommodation. Clearly the message was Booker T. Washington did not rock the boat and neither should I.

When one is living inside of an oppressive society a special psychology develops called the Manichean psychology. According to Hussein A. Bulhan, “The Manichean psychology permeates the prevailing values and beliefs. The oppressor identifies himself in terms of the sublime and beauty while depicting the oppressed in terms of absolute evil and ugliness.”

This creates a worldview where the group doing the oppressing, in America this means white people, is always the example of everything positive. It is aligned with the White Racial Frame in teaching us that whites and everything related to whites is superior. There is an old adage in the black community that we would prefer to buy our ice from the white man because his ice is colder than that purchased from the black man.

The neighborhoods where whites lived are the “good” ones. Schools that have a majority of white students are “good” schools. White women in this system of thinking personify the image of beauty. This image of beauty has shifted and some black women, who almost always have light skin, are now considered to be beautiful. Dark girls are still not considered beautiful within this Manichean psychology.

There is a clear line of demarcation that separates good from bad in oppressive societies like in America. Depending on which side of the color line you are on will determine how you are taught to see yourself.

Those who know me well are aware that my favorite two books are Ralph Ellison’s 1952 classic Invisible Man and Hussein Bulhan’s masterpiece Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Oppression. Both books look at the impossible task of living as a black person in America. I say impossible in a rhetorical way. To live as a person of color in America requires one to live in a world of alienation.

“The oppressor without becomes an oppressor within. The well-known inferiority complex of the oppressed originates in this process of internalization. Because of this internalization and its attendant but repressed rage, the oppressed may act out, on each other, the very violence imposed on them. They become autopressors as they engage in self-destructive behavior injurious to themselves, their loved ones and their neighbors.” – Hussein A. Bulhan in Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Oppression

Speaking about the impact of the Middle Passage, the violent journey of millions of kidnapped Africans to the West to work for the enrichment of whites, Bulhan talks about what it did to these African people.

“The Middle passage uprooted bodies, transporting them to alien lands… dislocated pysches, imposing an alien worldview… the uprooting of psyches from their culture to their insertion into another, in which the basic values were prowhite and antiblack, elicited a victimization difficult to quantify but very massive…to acquiesce to and embrace the oppressor’s culture, leaving behind what is left of one’s own is to plunge oneself into profound alienation in all its varieties and anguish.”

The same could be said of the untold numbers of Mexicans who woke up the day after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. They were citizens of Mexico one day and Americans the next. Mexico ceded fifty-five percent of its territory by signing this treaty and leaving many of its citizens in what would become the states of Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. The descendants of these Mexicans are still constantly being called “illegals” and told to “go back” to where they came from. They are literally aliens in their ancestral lands.

Bulhan talks about what occurs for those who are alienated in a society that never fully accepts them for who they are. It is a daily struggle to fit in. It is a constant balancing act to fit the white middle class values thrust upon people of color. It requires developing the skills known as code switching where people of color switch back and forth from being whom they are to being who whites accept them as.

“The school, the history books, the comic strips, the theatre halls—all these enforce cognitive dissonance and even self-hate…The schoolboy gets to the social circle of the oppressor, the more he learns to disparage what he is by birth and race. On the one hand, he is assimilated into the dominant culture, and on the other, he is made to break away from his own culture. As he moves through various stages of…education, he progressively reduces his contact with his relatives and indigenous culture…he increasingly enters the social orbit of the oppressors. Then comes the stage when he must choose either his own group and culture or the ruling group and its alien outlook…Acceptance of one entails rejection of the other; a gain in some respects involves a loss in others.

This is the daily struggle people of color find themselves fighting in America. According to Bulhan, “the oppressed community loses a member, suffers brain-drain, and risks betrayal by one of its own.”

Bulhan tells us that Fanon believed “it is particularly when the black person is cut off from his community and thrown into the white world that structural, institutional and personal violence intensifies.”

“Those who fear physical death and submit to oppression invariably condemn themselves to psychological, social and historical death. The oppressed submit out of fear of physical death, but because they submit, they become ill more frequently and die at an earlier age.”

Much of what we see in the lives of people of color in America is the result of these daily struggles. We are rarely allowed to be comfortable in our skin. As black people we are allowed to be respected entertainers and athletes. It is rare that we gain fame or acceptance in other spaces as black people.

I recently read an article where a member of the Boston Celtics team was leaving the arena after a game and a white “fan” got mad at him and called him nigger. This same person probably cheered him on the floor as he provided that night’s entertainment, but ultimately wanted him to know in no uncertain terms that he was only to be respected in that space.

People of color in America will always fight this battle to belong and to fit in. Some of us will choose the assimilationist route of Booker T. Washington. Some will reject assimilation and live within the realm of their cultural norms and celebrate their heritage. They will take the chance and be okay with not being accepted by white America.

“In the case of the American Negro, from the moment you are born every stick and stone, every face, is white. Since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose you are, too. It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, 6, or 7 to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to see Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, and although you are rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians are you.” – James Baldwin

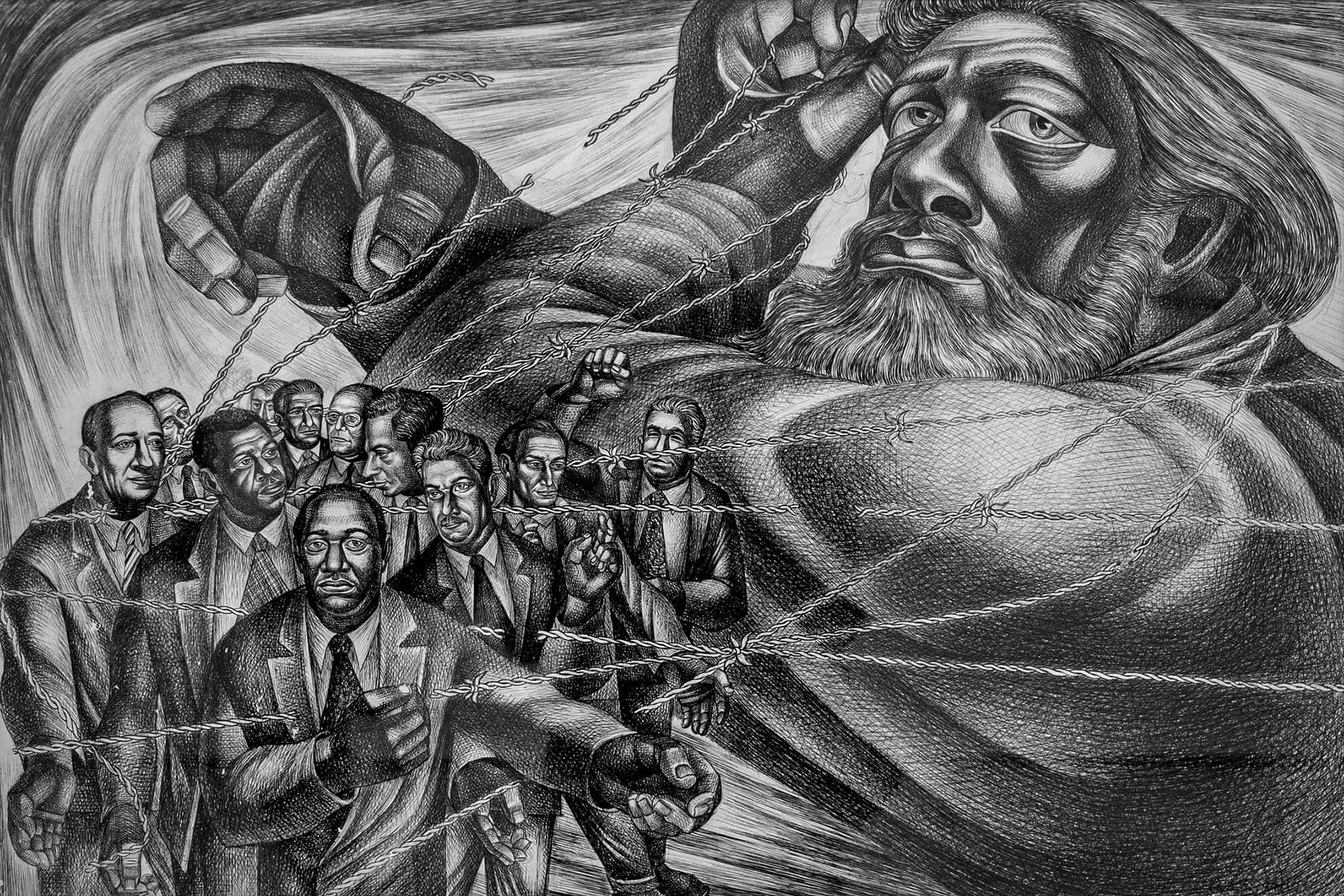

© Art

The Charles White Archives