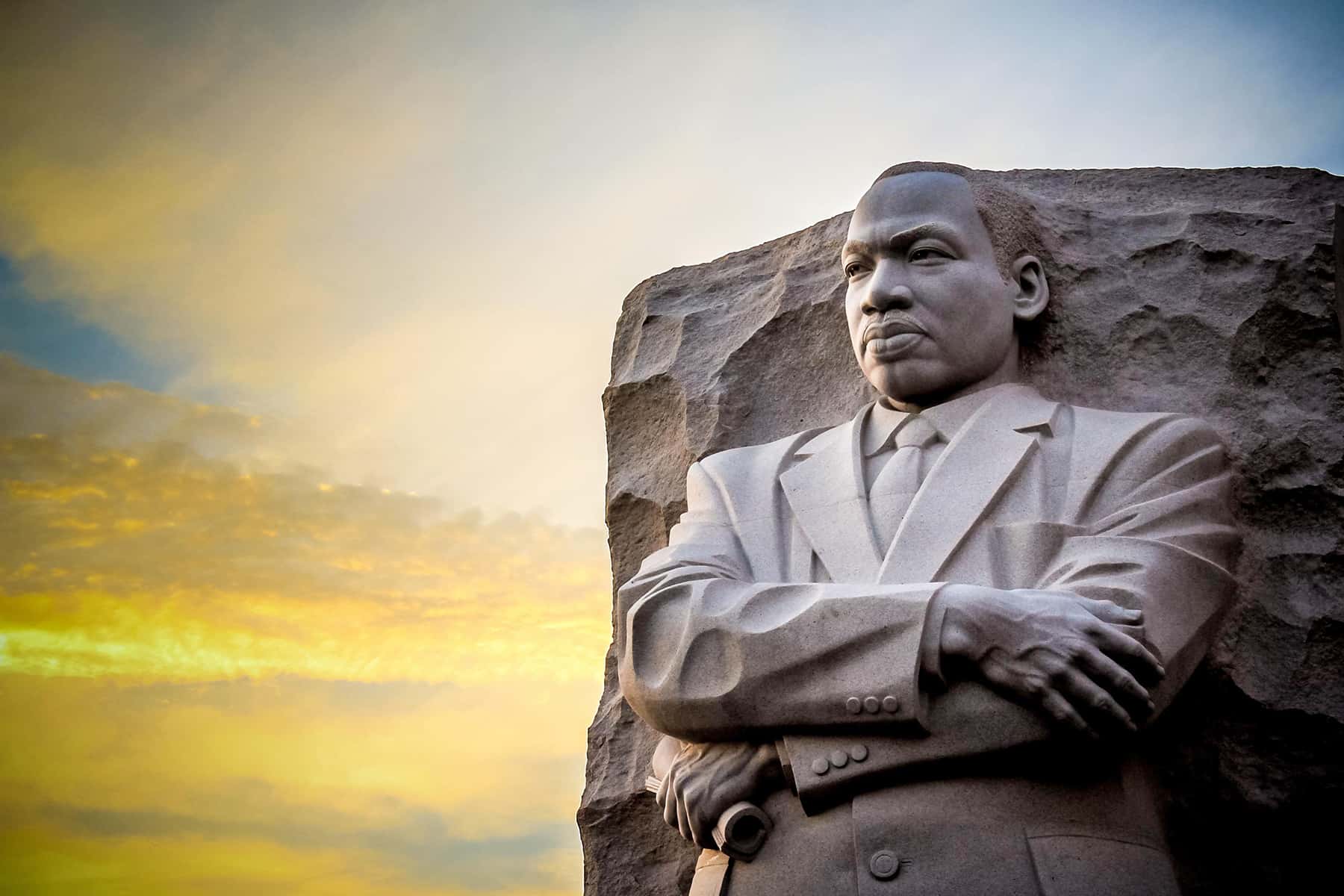

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” – Rev. Dr. Martin Luther Jr. August 28, 1963

This one sentence from the speech Dr. King gave at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom has been used to claim Dr. King was calling for a colorblind society. My belief, based on a reading of the entire speech, leads me to another conclusion about the use of colorblindness.

This takes some unpacking because of the way we’ve been taught to interpret the speech. First of all, the part of the speech about his dream was not even included in the written speech he prepared for that day. He ad-libbed that part because Mahalia Jackson shouted for him to “Tell them about the dream Martin! Tell them about the dream!” His speech that day was supposed to be short, only five minutes long, the limit all speakers were given that day, but he spoke for over 16 minutes.

As he struggled to come up with a theme, two metaphors were most prevalent in his mind. The one he went with in the written speech was the image of America having written a “bad check” to its black citizens. He decided he did not have time to use the dream metaphor in a five-minute speech. He made the decision to use American history to teach us a lesson about broken promises instead.

“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.”

These words were spoken just over two minutes into the speech. He wanted to use the promises of the Declaration of Independence and Emancipation Proclamation to illuminate the meaning of the “bad check” metaphor. Nearly fifteen seconds of enthusiastic applause followed this part of the speech. He continued that theme by saying:

“But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

Another ten seconds of uninterrupted applause and positive affirmations from the crowd followed these words. Most Americans have never heard this part of the speech. When I was taught the speech in school I only remember hearing the part about his dream. Most schools today still only use the dream part of the speech to honor the March on Washington. Every year on his birthday that part of the speech will be used to celebrate his life and dream. Liberals and conservatives alike use the words of Dr. King’s dream as a way of supporting colorblindness.

The message he planned to send that day resonated with the audience even before he went off script at the end to talk about the dream. There are multiple times during the speech in which he has to pause as the audience cheers and applauds his words.

His message that day was about the “bad check,” but most of us have never heard, read or been taught about that part of the speech. If you look up a video of the speech most versions include just the dream part of the speech, completely skipping over the main idea that he planned to deliver that day.

King had used some version of the dream metaphor multiple times as he preached prior to that famous day. He disregarded the end of his prepared speech and went well over the time limit to give a sermon that day. He couldn’t help himself: he was a preacher first and foremost. In April of that year while preaching at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, King used the dream metaphor. Deputies sent by the infamous Police Commissioner Bull Connor reported that King said: “that he had a dream of seeing little Negro boys and girls walking to school with little white boys and girls, playing in the parks together and going swimming together.”

Just eighteen days after the March on Washington, the church was bombed. A dynamite bomb exploded as the church was preparing to celebrate the “Youth Sunday” service. The church clock stopped at 10:25 a.m. Four black girls, 14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson and 11-year-old Denise McNair were killed and dozens of people were injured. Sarah Collins the 12-year-old sister of Addie Mae Collins was in the bathroom with the other girls and lost her right eye in the bombing and still has shards of glass embedded in her left eye. The bombing blinded her in both eyes and eventually she had to have the right eye removed in order to maintain sight in her left eye. She would say years later, “The way they treated me here in the city of Birmingham, they don’t acknowledge me as being the fifth little girl.”

Dr. King once again used the dream metaphor in Detroit in June at Cobb Hall when he said, “I have a dream this afternoon that there will be a day that we will no longer face the atrocities that Emmett Till had to face or Medgar Evers had to face, that all men can live with dignity… I have a dream this afternoon that one day, right here in Detroit, Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere that their money will carry them and they will be able to get a job.”

Only two and a half months before the march Mississippi NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers had been gunned down in his driveway on June 12, 1963. There was a great deal of anger within the black community leading up to the march that August. As a result the leaders of the march heavily censored the speeches given that day. They wanted to make sure that no one, including Dr. King, said something too controversial.

John Lewis the 23-year old chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was the youngest person to speak that day. Lewis had gained prominence in the organization after the Nashville lunch-counter campaign in 1960 and was one of the Freedom Riders attacked in Rock Hill, South Carolina in 1961. That courageous group sought to test a 1960 decision by the Supreme Court in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation of interstate transportation facilities, including bus terminals, was unconstitutional.

As with all of the speeches, a committee of the march’s organizers screened each one ahead of them being printed and handed to march participants and the press. They were not happy with the draft Lewis sent them. He spoke out against the Kennedy administration and used what many considered inflammatory language.

“We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently,” Lewis wrote in the original draft of his speech. Several people, Washington’s Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers and NAACP Chairman Roy Wilkins all complained about the tone of Lewis’ speech. A Phillip Randolph, who conceived of the march to shut down Washington D.C. in January 1941 as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union stepped in to resolve the controversy.

Lewis gave an incredible speech that day. His speech has been overshadowed by the one Dr. King is remembered for. He toned down the criticism of the Kennedy administration but still spoke of a lack of real leadership in Washington related to the civil rights bill being debated in Congress.

“It is true that we support the administration’s civil rights bill. We support it with great reservations, however. Unless Title III is put in this bill, there is nothing to protect the young children and old women who must face police dogs and fire hoses in the South while they engage in peaceful demonstrations. In its present form, this bill will not protect the citizens of Danville, Virginia, who must live in constant fear of a police state. It will not protect the hundreds and thousands of people that have been arrested on trumped charges… As it stands now, the voting section of this bill will not help the thousands of black people who want to vote. It will not help the citizens of Mississippi, of Alabama and Georgia, who are qualified to vote, but lack a sixth-grade education. “One man, one vote” is the African cry. It is ours too. It must be ours! … what political leader can stand up and say, “My party is the party of principles”? For the party of Kennedy is also the party of Eastland… Where is our party? Where is the political party that will make it unnecessary to march on Washington?”

A. Phillip Randolph in his speech also spoke eloquently about the need for jobs, which is still one of the major issues in the black community. “And we know that we have no future in a society in which 6 million black and white people are unemployed and millions more live in poverty. Nor is the goal of our civil rights revolution merely the passage of civil rights legislation. Yes, we want all public accommodations open to all citizens, but those accommodations will mean little to those who cannot afford to use them. Yes, we want a Fair Employment Practice Act, but what good will it do if profit-geared automation destroys the jobs of millions of workers black and white?”

Lewis is the only speaker that day to use the word black instead of Negro. Malcolm X was not a fan of the march. He criticized the leaders of the march who were called to the White House by President Kennedy. They are commonly known as the Big Six: Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); James Farmer Jr., of the Congress Of Racial Equality (CORE); John Lewis of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); the National Urban League’s Whitney Young, Jr.; and Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and A. Phillip Randolph.

Kennedy was concerned about the march leading to violence and called the Big Six to the White House to express his concerns and get assurances that the march would be well controlled. Malcolm X, who attended the march, facetiously called it the “Farce on Washington.” In his autobiography he described how Kennedy and rich white donors had softened the militancy of those who advocated for the march early on. He said Kennedy tried to shut the march down but was told by the Big Six that they could not do so. He complained about the march being toned down and controlled by having only approved signs carried that day. Looking at images of the march I noticed that most of the signs were the same. These are the ones that you see in all images of the march. There were some with different messages but they are relatively few in number compared to these.

“We demand an end to bias now!”

“We march for integrated schools now!”

“We march for jobs for all now!”

“We demand decent housing now!”

“We demand an FEPC law now!”

“We march for jobs for all a decent pay now!”

“We march for higher minimum wages coverage for all workers now!”

Malcolm X in his autobiography said this about the march:

“The marchers had been instructed to bring no signs–signs were provided. They had been told to sing one song: “We Shall Overcome.” They had been told how to arrive, when, where to arrive, where to assemble, when to start marching, the route to march… Yes, I was there. I observed that circus. Who ever heard of angry revolutionists all harmonizing “We Shall Overcome. . .Suum Day. . .” while tripping and swaying along arm-in-arm with the very people they were supposed to be angrily revolting against? Who ever heard of angry revolutionists swinging their bare feet together with their oppressor in lily-pad park pools, with gospels and guitars and “I Have A Dream” speeches? And the black masses in America were–and still are–having a nightmare.”

Dr. King did something unusual for himself with his speech that day. He asked for input from his close advisors in drafting the speech. Knowing he had only five minutes, he used the metaphor of the “bad check” as his main point in the speech. The draft of the speech in which Dr. King finished at about 4 a.m. the night before, included nothing about his dream. His advisors typed the speech and passed it to the press without the words “I have a dream” anywhere in it.

Mahalia Jackson’s request led King to discard the rest of his speech and he used his improvisational skills to deliver the words that we’ve all heard. The words, which define Dr. King’s life work in the minds of many, he never intended to speak that day. He was asked about why he used the dream metaphor and responded, “all of a sudden this thing came to me that I have used — I’d used many times before, that thing about ‘I have a dream’ — and I just felt that I wanted to use it here.”

Getting back to the improvised part, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” has a different meaning when placed into context.

The message Dr. King was sharing during the speech is that America had created a nation where the color of skin led to discrimination against blacks and privileges for whites. He did not want us to be colorblind but instead wanted us to understand how color conscious the nation was. Black skin was a badge of dishonor. White skin was a key to access the “the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” King wanted everyone to have access to these privileges.

This important message from Dr. King has been left out of the narrative of the speech. Dr. King’s legacy has been defined by far too many by an improvised part of his speech. Learning the sanitized version of the speech has cheated us from understanding who Dr. King really was. That speech was not the last of his life but most people have not heard any of the other powerful speeches he gave, except for the “Been to the Mountaintop” speech he gave the night before he was assassinated.

As I’ve traveled around the country white people have told me that they were taught to be colorblind. They were told this was a must fair way of judging people. “Color doesn’t matter!” they’ve been told. In the real world it does matter. In America it always has mattered. Assuming it does not matter, allows people to dismiss the lived experiences of people of color. Centuries of discrimination faced by people of color throughout American history simply because they are not white can be ignored. When someone says to me “I don’t see color.” it does not resonate as something positive with me. Instead, I hear that the fact that I’ve faced discrimination and my family members who came before me were enslaved, raped, murdered, segregated, and treated as less than human is not relevant. It unintentionally sends the wrong message.

Colorblindness has been used to dismiss the lived experiences of people of color for far too long. It’s time we stop pretending to be colorblind and telling people we don’t see color. We all see color. If we use what we see to give different levels of value to people based on the color of their skin that’s problematic.

Let’s retire the concept of colorblindness and understand that we can use what we see to do something other than making negative judgments of others. Let’s focus on these words of the speech as we teach it to our children and try to discern what Dr. King’s real message that day was.

“There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating for whites only. We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Support Us

Our mission of transformative journalism means that we are editorially independent. Our staff determines what is important news to report on, and in what voice to speak on issues. No one influences our opinion, and no one edits our editors. We are free from commercial bias and are not influenced by corporate interests, political affiliations, or a public preferences that rewards clicks with revenue. As an influential publication that provides Milwaukee with quality journalism, we depend on public support to fulfill our purpose. Our award-winning photojournalism, columns, interviews, and features have helped to achieve a range of positive social impact that enriches our community. Please join our effort by entrusting us with your contribution. Your Support Matters – Donate Now