“We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.” – Winston Churchill

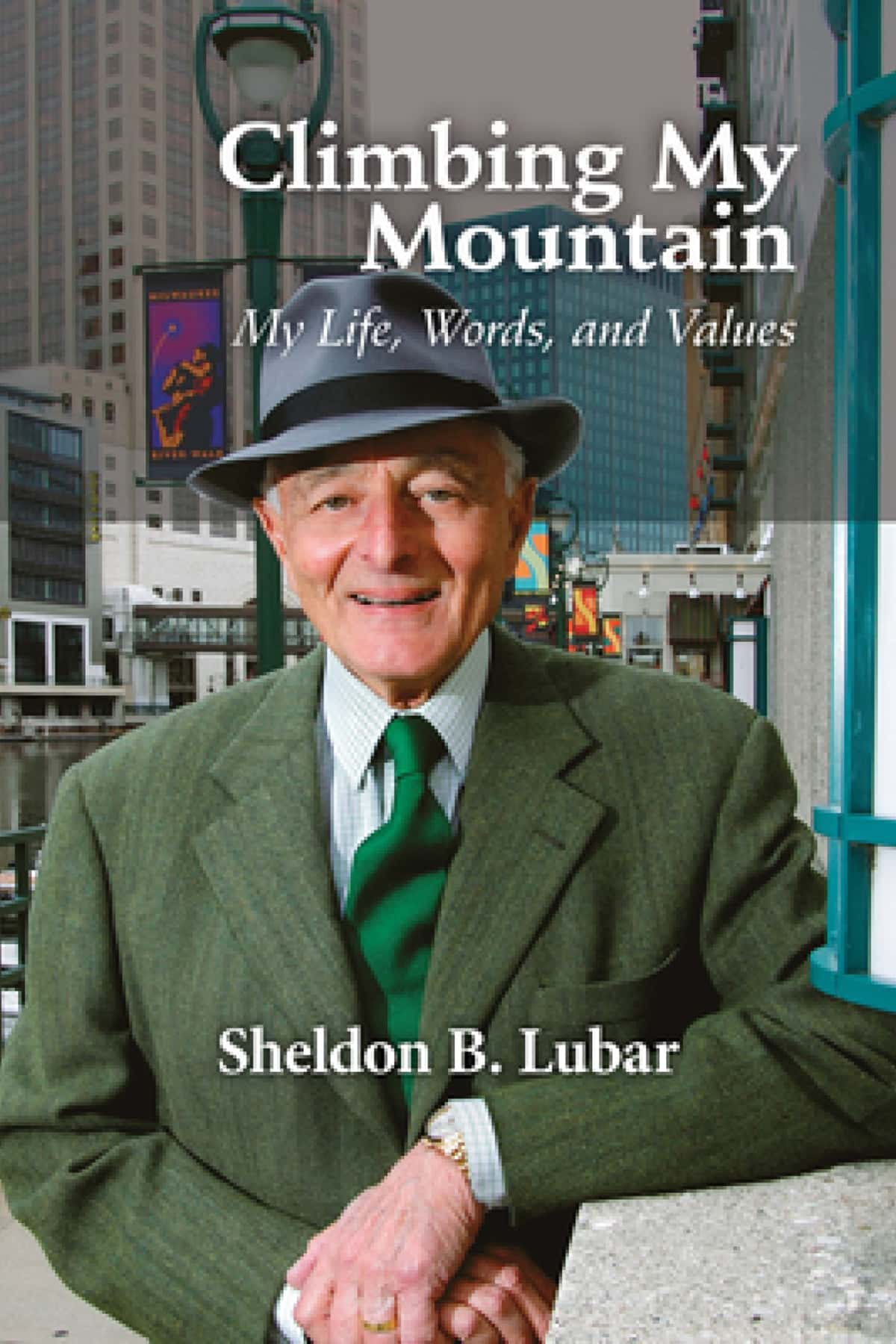

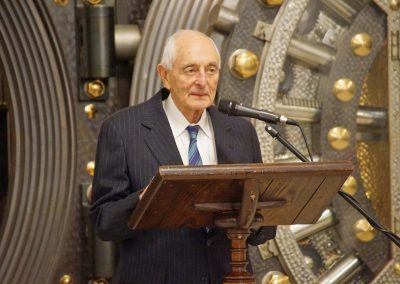

The book Climbing My Mountain: My Life, Words, and Values by Sheldon Bernard Lubar Ph.D. was officially released during a public party last month at the Milwaukee County Historical Society. The new memoir details the experiences, successes, and deeply held principles from one of Wisconsin’s leading entrepreneurs and most generous philanthropists.

In his ninetieth year, the renowned civic leader penned an account of his life and in a refreshingly candid record. The book is divided into two parts, separated by a photo essay with visual highlights from his life. Part One is a revealing memoir that describes Lubar’s journey as a businessman, husband, father, and citizen. Part Two consists of speeches he delivered over the years, ranging in topic from the life of an entrepreneur to the state of the American economy.

“Lubar’s counsel is widely sought and universally respected, and his impact on education, the arts and public policy has been profound. When Sheldon Lubar talks, people listen. When Sheldon Lubar writes, people should read.”

– John Gurda, Historian

The motivation to write about his memories gave Lubar the opportunity to rethink how his life and career developed, and offer readers an understanding into that adventure. Lubar defines himself as someone who believes strongly in lifelong education, self-discipline, and enlightened self-interest. As a capitalist, he believes in saving, investing, and postponing the consumption of wealth for the reward of building a greater future.

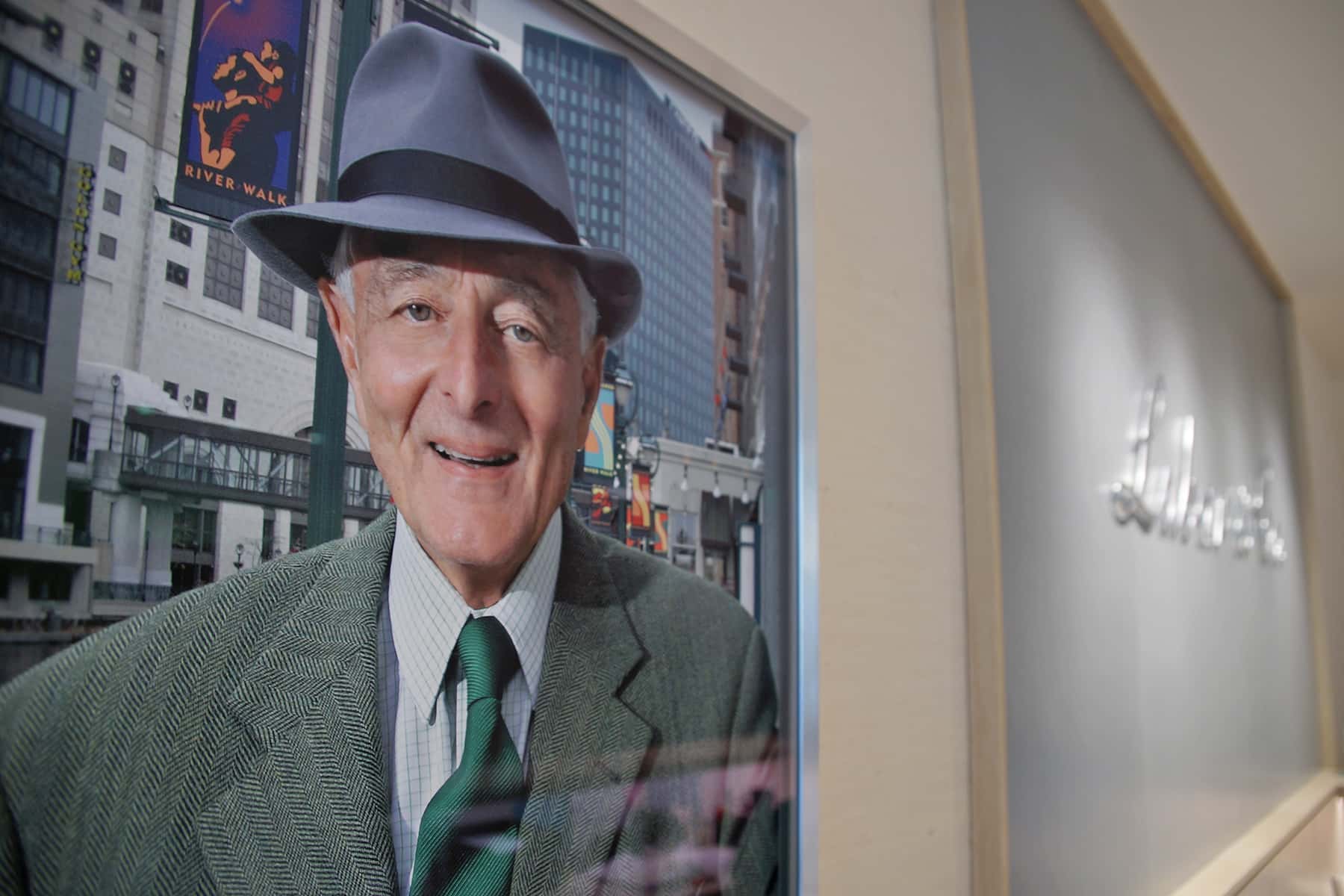

Sheldon B. Lubar is the founder and chairman of Lubar & Co., a private investment and wealth management firm based in Milwaukee. Widely known in financial circles, Lubar also has a distinguished record of public service. His book is not literally about mountain climbing, although he does talk about enjoying that recreation. Instead, it is an expression of a life driven by moral values, with the title as a metaphor for an insightful reflection of his journey.

The Milwaukee Independent recently sat down with Sheldon Lubar, in his office overlooking the Henry Maier Festival Park, to talk more about his Milwaukee experiences.

Q&A with Sheldon Lubar

Milwaukee Independent: At 90 years old, you have had decades of adventures mixed with some tragedies along the way, so what was the process like to write a memoir that covered such an enduring life experience?

Sheldon Lubar: Well, I really enjoyed writing it. As a matter of fact, when I finished the book I thought about how much I enjoyed it. I wrote almost everything entirely from memory. I had notes from the many speeches I’ve made, and my date book for reference so that I could identify where I was at any time. But for the most part, I wrote from memory and I truly enjoyed that. I also thought maybe I’ll write another book, but it’ll be about something else besides myself. After the books were published, I gave copies to the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee for the students to use, because there’s a lot they can learn from reading it.

Milwaukee Independent: You have subscribed to the phrase by Heraclitus that “Nothing endures but change,” so how have you adapted to change in your life? And what secret would you share with people who resist change?

Sheldon Lubar: I think I tried to anticipate change, and I’ve never had a long term plan. I didn’t start out saying I wanted to be rich, nor did I start out saying I wanted to be poor. I started out wanting to do something that I was proud of. My wife and I were married when both of us were relatively young. I was in my very early 20s, and Marianne was 19. So I also wanted to be able to support my family, and I looked forward to having children. I wanted to have as many children as my wife could handle. So I never had a long term plan, but I did always have a short term plan and I would stick to it. Meanwhile, I would look ahead to the next thing I would do, and then the next thing. I was always reading, so I was well aware of what was happening, not only in my community but in the world.

Milwaukee Independent: What do you see as the biggest challenge for Milwaukee’s future, and what efforts or investments can be made to ensure that residents evenly benefit from any economic success?

Sheldon Lubar: In my book I pointed out one of the advantages I had, which I would hope that every newborn child would have two loving parents to give them guidance. None of us knows anything at birth, and what we develop is a combination of our encounters and attempts at learning and education. I consider learning to be a lifelong activity and enterprise. It’s something I love doing, I love discovering something I didn’t know. And for that we all need guidance, we all need help. That help initially comes from our parents. I know my parents loved me and my two older sisters. They said, what you learn and what you have in your head is always yours, no one can take it away from you. That is what you have to take with you. So if you’re an immigrant coming from some place, they may not let you take things across the border, except what knowledge is in your own head, your memories, and your experiences. When I see what the problems are in our city, the problems in the Milwaukee Public School System, and too many children growing up in a household without two parents, it’s clear how important education and learning is. It’s pretty hard for a single parent, especially a single parent who has to work, to have the time or maybe even the ability to guide a child. So if we want to solve the problems of our society, the cure doesn’t come quickly or by handouts – that is helping somebody when they need help. To make a life, that takes the foundation of education.

Milwaukee Independent: Your mother’s family lived in the Haymarket area of Milwaukee, which in the vernacular of the time was considered a Jewish ghetto, so what was their experience like adapting to a new country and particularly a diversely immigrant city like Milwaukee?

Sheldon Lubar: I really don’t know much about their experience. My mother went to the Fourth Street School, which is now known as the Golda Meir School. And, one of her brothers actually married Golda Meir’s sister. My mother went to the School of Secretarial Studies at the Spencerian Business College. After school, my mother went to work at Gimbals. My grandfather, her father, died a week after I was born so I never got to know him. I don’t know much else, except they were pretty happy. When my father came here, he had graduated from high school. He had two older brothers who preceded him to Milwaukee some years earlier. He had lived in Russia, in an area that is now Ukraine. I asked him once about his life there, and he said that he loved it. I then asked why he decided to come here? He told me that his father had died when he was only eight years old, and his mother died just as he graduated from high school. So he wanted to be with his brothers. When he came here he worked at the Wisconsin Hotel, and he drove a taxi cab for a while. Then he was drafted into the Army for World War I and went to France. He stayed there for two years, and was in the trenches for more than a year. He was wounded twice and stayed an extra year with the American regiment. When he came back to Milwaukee, he started a business with a brother-in-law. I admired him enormously. I think my father was a happy man, and he was a no nonsense man, a two fisted man as we’d say. If anyone gave him lip about being Jewish, they regretted it.

Milwaukee Independent: How has the Jewish community of Milwaukee changed in your lifetime, particularly around the Sherman Park area and even Whitefish Bay?

Sheldon Lubar: For me, it didn’t change too much. We lived on Sherman Boulevard, directly across the street from the south end of Sherman Park – where I would play when I was little. I went to Townsend Street Grade School, which was two years of kindergarten and then through fourth grade. There were no students of color in my classes, because there were very few African Americans in Milwaukee at that time. Then we moved to Whitefish Bay on the east side and I went to Cumberland Elementary School. I had a lot of Catholic friends and a lot of Jewish friends who were from all over, not just Whitefish Bay. It was a wonderful experience growing up in both places, and I have only the best memories of those days.

Milwaukee Independent: You were president of Summerfest early on at its beginning, so what is your fondest memory of that experience? And what are your thoughts of what it has become today?

Sheldon Lubar: Summerfest was Mayor Henry Maier’s first love and dream, but he wasn’t a great organizer. It was originally kind of scattered throughout the community. It was held at the Milwaukee Road Railway Station, then at this park or that park. But it was my predecessor John Kelly who got it all collected down on the Lakefront. As director he hired Henry Jordan, who had been an All-Star Hall of Fame football player with the Green Bay Packers, and he was wonderful. That was the first big success. I succeeded John Kelly and did it for a year, with Henry Jordan as my director. But I’ll tell you, I was very worried because we had no money. When John Kelly started, I think they had a deficit and he worked out of that. So it was kind of even up when I started. I just remember that I was worried to death, since we had made $700,000 of commitments. Then the first day of SummerFest it poured rain, like the heavens opened up on us, and it wasn’t sunny. But it all worked out and we showed a profit. That was the beginning of what’s developed into a lot more. Henry Meyer was very supportive of it, and the police were helpful. It was a fun and a gratifying thing to do, but I was overjoyed when it was over. I have never been to it since, and from my office I can look down and see the Summerfest grounds. But I still remember what we had then, with the Pabst Pavilion, and just how happy we were with this new thing that people would come to from all over the United States and even further.

Milwaukee Independent: What is your fascination with the Rocky Mountains, and mountain climbing in general? And what mountain do you still have left to climb, either literally or metaphorically?

Sheldon Lubar: As a boy I think I was quite typical. I loved American history and I would read about the development of the West, and what it meant for the creation of America. All those stories about frontier hardships by the immigrants who built our nation, it really fascinated me. That period of Western Expansion saw a mass migration through the wilderness, when settlers had to overcome so many obstacles, like mountains. I hadn’t seen any mountains growing up. When I did see them after I graduated from high school, I thought they were awesome. I loved all the stories of the mountain men, and the cowboys, and the Western lore. When I was older, and I took up skiing, I was absolutely in love with the mountains. I decided that’s what I wanted to do, to spend all my time skiing. Then in the summer I started hiking in the mountains. I would go up the Rocky Mountains every day I could, and tried to reach the top. If it started snowing or got too rainy at night, I’d turn around and come back later. All so I could reach the top and look around at the wonderful view. Later I would take my children with me, but more often than not, I did it alone. Then I started thinking of doing higher mountains, and I took some instruction to do that. I’m no great mountain climber, but I’ve climbed a lot of high mountain.

Milwaukee Independent: You had a job interview with John Dean, when you served in the presidential administration of Richard Nixon. So what is your fondest memory of that time, and what was that experience like as Watergate unfolded?

Sheldon Lubar: I was there in the second Nixon-Ford administration. As for Watergate, it had already happened but that was a period of retribution, and the President was ultimately forced to resign. It didn’t really bother what I was doing, because I was not political at all. I was recruited for the position because I had been the CEO of a very successful mortgage banking firm. Our business was originating FHA and VA insured loans, so I knew all the government housing programs and was making single family residential loans. As a result, I knew the secondary markets for these loans where these loans would be sold. So I was known as somebody who had great knowledge of the mortgage markets, and how to work with the Housing and Urban Development Department of the government. Also at that time, they were going to produce the most thorough research study of housing in the United States that had ever been done in order to proposed new legislation. So I was recruited to fill in a spot that had to do with the funding and financing of it. I don’t know for sure how they ever got my name, but I can guess what happened. One day in the summer of 1973, I received a phone call from the White House. It was interesting that they somehow found me in Aspen. We had just bought a home there. My wife and our four children had come out a day before me. When I arrived I asked what was new, and my wife said I got a phone call from the White House. And she was not joking. So I called them back and the man on the other side said, ‘Mr. Lubar, we understand that you could be available, because there was announcement in the Wall Street Journal – a small article that our company was being acquired by a bank in the east. And we understand that you could be available to do a job for your country. Are you willing to consider that?’ A thousand thoughts went through my head, but I said ‘of course, what is the job?’ He said I’d be Assistant Secretary for Housing Production and Mortgage Credit, Commissioner of the Federal Housing Administration, a director of the Federal National Mortgage Association, and the government’s National Mortgage Association would be responsible to me. So I said that I wanted to think about it and call him back. Well, our four children were right there alongside my wife. We’d just moved in, so we didn’t even have a table. We had a big packing box that pillows came in. So we sat around our makeshift paper box table and I proposed the alternative. We could go to Washington and have another adventure, because just maybe six months before that I had finished a one year sabbatical. We had moved to Switzerland – and that really got me into mountain climbing. So I said we could go to Washington or I could babysit our merger in Milwaukee, and we’ll be happy as clams. What do you think? And they unanimously said, ‘let’s have another adventure.’ So I called him back and I said I’d be interested, and he invited me to come to Washington and be interviewed. And that’s what I did.

Milwaukee Independent: You went on to serve under Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, so why did you not pursue a political career of your own after that?

Sheldon Lubar: You have to be a real optimist to have a look at things permanently there. And to be quite frank, I wanted to go home. We did our housing study, and I have never worked as hard as I did before or since on anything. We were going every day, all day, from dawn until midnight. I was reading stacks of papers on every subject possible, public housing, and cities, and everything. When it was done, we wrote legislation that is still largely the law of the land today. That was over 1973 and 1974, and meanwhile, President Nixon is in the White House and he’s going through the aftermath of Watergate. They were preparing to get rid of him, and he did resign. But our legislation was written. We were Republicans and the Congress was all Democrats. Jim Lynn, who was Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, and I went around to the House and the Senate and worked with the everyone to pass our legislation. Now, Republicans and Democrats can’t even speak to each other in a civil way. Anyway, the legislation was passed, the president left, and I’m did not thinking in terms of a permanent career in politics. Then Gaylord Nelson, who was our senator from Wisconsin and had just started Earth Day got in touch with me. He was a brilliant man, one of the great senators of all time, and he was the man that really started talking about climate change way back then. He was chairman of the Senate Small Business Committee, and he talked to President Jimmy Carter about having a White House Conference on small business. Gaylord told him that I was the man he wanted to be the chairman of this. Jimmy Carter said, ‘This guy was in the Nixon administration, I can’t take him.’ But Gaylord said I was his man. So I was still brought in, but not as the Chairman. I met Jimmy Carter and I liked him a lot, and I think we did a great job. We came out with a report that showed how all of the net new jobs in the United States were created by small businesses. I think that’s probably still the case today, and that means we need more entrepreneurs, more people who start businesses. And, so many new businesses are started by immigrants, because nobody else will hire them.

Milwaukee Independent: Housing has been an important element of your career, and you know how the 2008 real estate bubble devastated America, and particularly Milwaukee which suffers racial inequity. Then, why is it so hard to get people affordable housing who need it?

Sheldon Lubar: When I came to Washington, a lot of markets were just awful. The first thing I was presented with at the Federal Housing Administration was what had been an architectural prize. It had won all sorts of acclaim when it was built in 1954. It was a complex of 12 high rise buildings in St. Louis called Pruitt-Igoe, and it was all public housing. But in under 20 years it had deteriorated to the point that police would no longer go there. They would get shot at from snipers on the upper floors. There were fires in the building, but the firemen would no longer go there because it wasn’t safe. The plumbing system was destroyed and the elevators didn’t work. It was uninhabitable. Pruitt-Igoe is what we called a warehouses of poor people. And one of the things that our housing study said was that low income people should not be packed in a warehouse. They should be distributed through the community, and that the FHA would certify safe and sanitary housing, and issue vouchers to low income people – and that would be affordable housing. So I signed the order to destroy Pruitt-Igoe and we got rid of a lot of those type of locations. Our our goal was to distribute affordable housing through a community, not to have concentrations of it. And to the best of my knowledge, I don’t know how that’s been managed since 1974.

Milwaukee Independent: What was the experience like to travel back with your father to his village in Russia during the Cold War?

Sheldon Lubar: My father was eighty years old and he wanted to go back to see his old village. I had tried the year before I went to Washington, and I couldn’t get visas to go to Ukraine. When I was interviewed by John Dean, he asked me if I had any conflicts of interest or commitments that I needed to fulfill. I told him I promised my father that I would take him back to his hometown in Ukraine, but I hadn’t been able to arrange it. He offered to help, and did. Henry Kissinger sent a cable to the our Ambassador in Moscow to enable Secretary Lubar and his father to go. They arranged it all as part of a goodwill visit, and we stayed in Moscow while I met my counterpart there – who had a much greater job than I did. I was just in housing, but he was in charge of all construction that went on in Russia. And he was very antagonistic toward me, blamed me for The Cold War. I had my father with me, and then they started talking. This guy was in World War Two, my father was in World War One. So they’re wondering, who was a better soldier? I was happy we had a translator between us. Then we flew to Kiev, along with this translator, and from there drove to the village of Rosava. We were met at the outskirts by the Mayor of the city, and a man who looked like he was with the secret police or something like that. When we went to into the village, my father recognized a little of it, and then he actually met somebody on the street. He was 80 years old then and he left when he was 18. So 60 years later, he runs into the daughter of the blacksmith of the town. It was the blacksmith that saved my father’s life by pulling him out of a frozen lake when he fell through the ice. He and the woman hugged and had tears in their eyes, and were amazed that they could identify each other after so many years. We stood there and talked for a couple hours, which made us late to a luncheon for us to speak about agriculture issues and things like that, as a goodwill effort to break down the cultural walls between us. We were shown around and the territory, which looked very similar to Wisconsin farmland. They showed my father where the Jewish cemetery was that the Nazis destroyed. And we saw a big community farm. They didn’t let us go out into the fields, but I could see all the workers there were women – wearing the Babushka headscarf and boots. The Ukrainians really suffered under Stalin, who starved so many millions. And that was after the millions of people lost during the war. So there was still a shortage of men, and women had to do a lot of the hard work.

Milwaukee Independent: So what advice do you have for Milwaukee entrepreneurs, particularly people of color or people who just don’t have really good business connections?

Sheldon Lubar: Every place is a good market for new ideas. The Number One and most important thing is to get an education. Go to college or a trade school and don’t borrow money, work your way through to stay out of debt. You can’t get a good job unless you get educated. Your type of education maybe learning a trade or a skill, but get something that you’re proud of. I feel very fortunate. I was so proud to tell my friends or whoever about my work. If you’re proud of what you do, you’re doing something worthwhile. Be independent and never stop learning. If you can’t afford college, go to work first and start taking courses, then pull yourself up and have a try to live your dreams. There’s so much opportunity here in Milwaukee, but you have to put in the effort. I was working all the time, but I never considered it work. I enjoyed it so much, it was fun. If you don’t love it, then you don’t do it.