By Jason Loviglio, Chair and Associate Professor of Media and Communication Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

From its start half a century ago, National Public Radio heralded a new approach to the sound of radio in the United States. NPR “would speak with many voices and many dialects,” according to “Purposes,” its founding document.

Written in 1970, this blueprint rang with emotional immediacy. NPR would go on the air for the first time a year later, on April 20, 1971.

NPR is sometimes mocked, perhaps most memorably in a 1998 “Saturday Night Live” sketch starring actor Alec Baldwin, for its staid sound production and its hosts’ carefully modulated vocal quality. But the nonprofit network’s commitment to including “many voices” hatched a small sonic revolution on the airwaves.

As a radio historian, I have written about the medium’s unique blend of intimate voices and public address. As the 50th anniversary of public radio draws near, I’m interested in NPR’s contradictory legacy of sonic innovation and monotony.

This is NPR

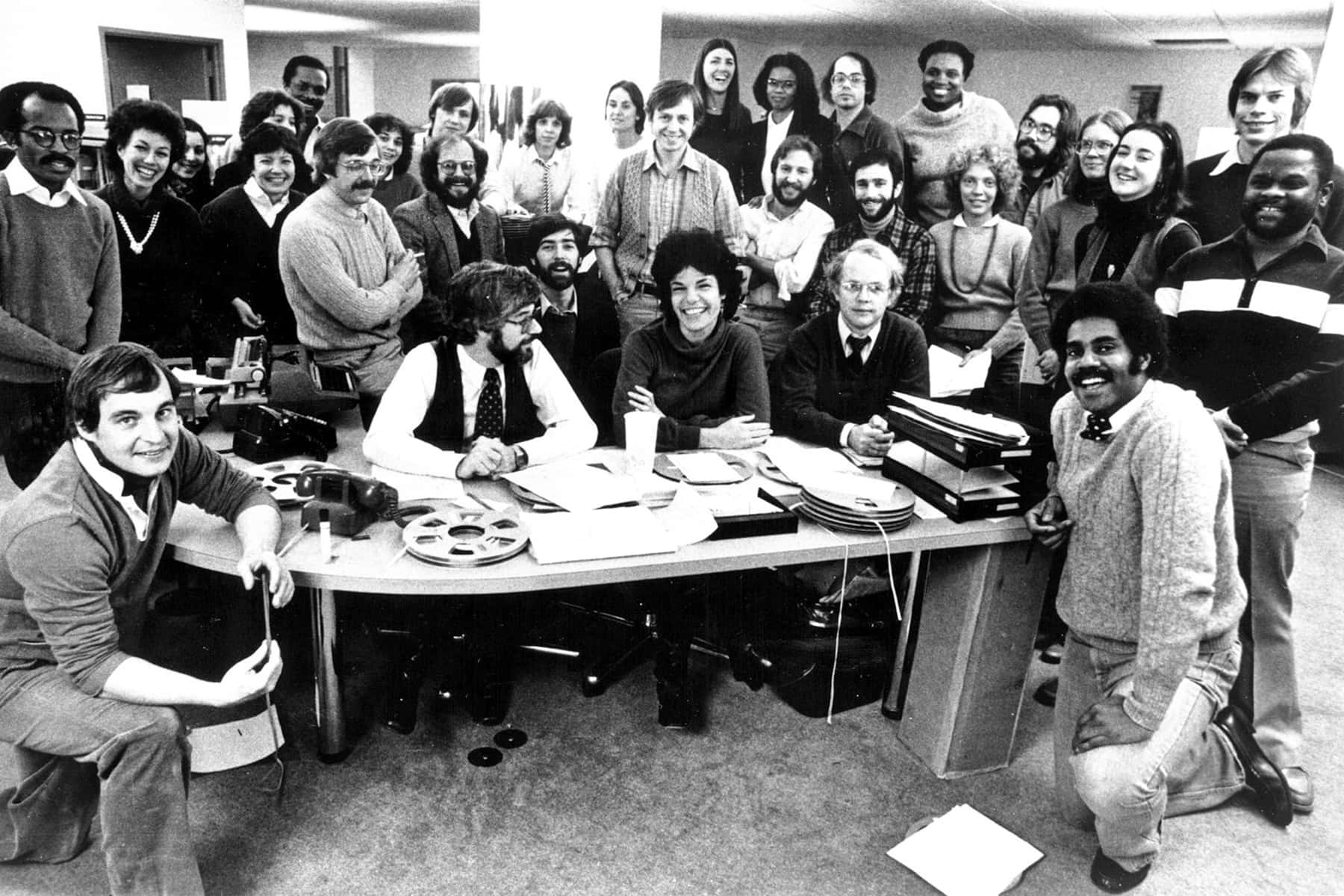

One of the first voices to become associated with NPR’s flagship evening news program was Susan Stamberg. Hired in 1971, she soon became the first woman to co-anchor a national nightly newscast on radio or television in U.S. history.

William Siemering, the network’s first program director and the author of “Purposes,” wanted the voice of the network to communicate curiosity rather than authority. Stamberg, 31 when she was hired, brought youthful exuberance to the job.

And, in another departure from newscasting’s baritones, with their supposedly neutral midwestern accents, Stamberg’s voice was “nasal, quizzical, and unashamedly female,” as Lisa Phillips put it. It came she said, “with a hometown – New York – and an ethnicity – Jewish.”

The decision to stick with young and relatively unproven voices came at a cost, according to Jack Mitchell, the original director of the “All Things Considered” evening newscast.

In his account of NPR’s beginnings, “Listener Supported,” Mitchell later recalled how Siemering passed up Ford Foundation funding tied to hiring the proven and respected newscaster Edward P. Morgan, a white man originally from Walla Walla, Washington. Instead, NPR stood by the less “authoritative” and more engaging voices of Stamberg and her peers, even if they sometimes sounded “less than professional.”

“Masculine, commanding” voices were “exactly how we DON’T want to sound,” Siemering told his staff, as Stamberg later recalled in “This Is NPR: The First Forty Years.”

Early feedback on Stamberg from station managers around the country wasn’t encouraging. She sounded too New York, too Jewish, too off-putting, Mitchell wrote. Siemering hid these negative reviews from Stamberg as she found her own broadcast voice, which helped her win many prestigious awards in broadcast and digital journalism. The network regards her as one of its “founding mothers.”

Women as anchors

NPR has kept speaking with many voices that would sound out of place on the air anywhere else. Many, if not most, have been female. As hosts and anchors, correspondents and reporters, women have played a key role in giving NPR its distinctive sound.

Nina Totenberg, Linda Wertheimer and Cokie Roberts brought hard-nosed journalism and inside-the-Beltway sensibility to the fledgling network in the 1970s. In the process, these white women changed what the news sounded like.

By the time Wertheimer took over as an “All Things Considered” co-anchor in 1989, it was no longer controversial to hear women deliver the news of the day.

But on network television, most of the early stints for the women who were the first to anchor daily news programs were short-lived. Barbara Walters lasted two years in the mid-1970s as an “ABC Evening News” co-anchor. Diane Sawyer co-anchored the “CBS Morning News,” from 1981 to 1984 and Katie Couric spent five years, starting in 2006, as the sole “CBS Evening News” anchor.

Curating distinctive voices “rich with the rhythms and accents of their regions” was another explicit way in which “All Things Considered” initially sought to sonically mark its difference from what had come before, according to Stamberg.

A wider range?

NPR’s commitment to many voices included those who brought regional, as well as gender, diversity to the airwaves. Occasional commentators Baxter Black, a cowboy poet from Texas; Vertamae Grosvenor, a culinary anthropologist born in the Gullah community of North Carolina; and Kim Williams, a naturalist, checked in during the late 1970s and early 1980s, with field reports from their corners of the country. Andrei Codrescu, a Romanian-American artist living in New Orleans, began to bring his thickly accented English and droll humor to NPR in 1983.

Putting these folks on air seemed to address the network’s vision of speaking in many voices and accents. The intent, Mitchell wrote, was explicitly democratic, to be “representative of the nation. That meant white, black, Hispanic, Asian and as many women as men.”

NPR’s growth led to the opening of foreign bureaus, even as print publications hemorrhaged these expensive positions. International coverage further expanded its vocal range. Some of the women now working as the network’s anchors got their start as foreign correspondents. Doualy Xaykaothao spent years reporting from Asia and Lulu Garcia-Navarro covered Latin America and the Middle East for NPR.

Other women with nonconventional news voices, including Eleanor Beardsley in Paris, Sylvia Poggioli in Rome and Ofeabia Quist-Arcton in Dakar, are still overseas. Their signature approach to signing off with their name and locale is a sonic pleasure for many NPR fans.

Even so, by the turn of the century, the network faced complaints about its tight control over pronunciation, cadence and accent, especially for women and people of color. Critics denounced a sense that the voices of NPR’s female journalists sounded “alike in their sober nasal condescension,” as the writer and actor Sarah Vowell put it – hinting at a class-related critique, along with a gendered one.

NPR’s women, some of these naysayers contend, have low-pitched voices that sound too much like men and that NPR voices in general sound more like each other than everyone else. Writer Scott Sherman calls it the “NPR drone.”

Even Stamberg said in a 2010 interview that one price of NPR’s success was that listeners weren’t “hearing great voices anymore.”

Another round of criticism, this one aimed primarily at young women, identified “vocal fry,” a low creaky way of speaking, as an irritating feature of public radio voices. The critique, which came mostly from men and older folks, suggested that despite what the critics were saying, NPR’s sound was not static but evolving.

NPR’s sonic palette and its range of voices has broadened in recent years, especially through its podcasts and on weekends – when Navarro, who is Latina, and Michel Martin, an African American woman, are two of the network’s main three news anchors.

Sam Sanders, an openly gay African American man, hosts a cultural talk show branded with his own name. Programs like “Alt.Latino” and “Radio Ambulante,” which are either in Spanish or in English punctuated with Spanish words, indicate that the network aims to serve new listeners.

As NPR looks forward to the next 50 years, its decisions over whose voices belong on the air will determine how well it lives up to its founding commitment to sound like America. And it is likely that criticism of how those voices sound will reflect dominant attitudes about who gets to speak.

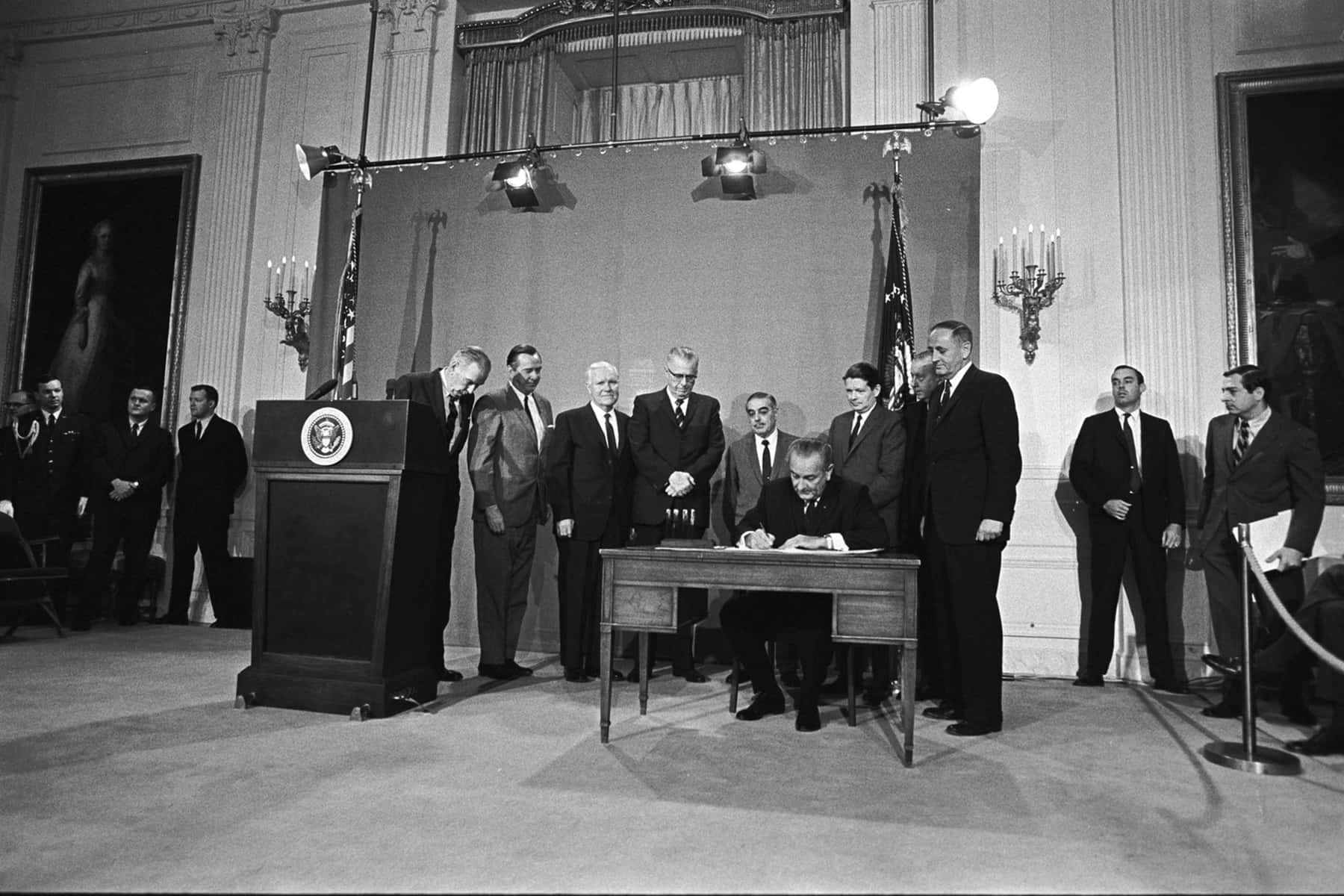

Yoichi Okamoto and NPR

Originally published on The Conversation as NPR is still expanding the range of what authority sounds like after 50 years

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.